BIM has established itself as a working methodology capable of generating tangible benefits throughout the entire construction process, from design to project management. Its growing popularity is linked to the advantages of BIM in terms of interdisciplinary coordination, error reduction, time and cost control, and higher quality design decisions.

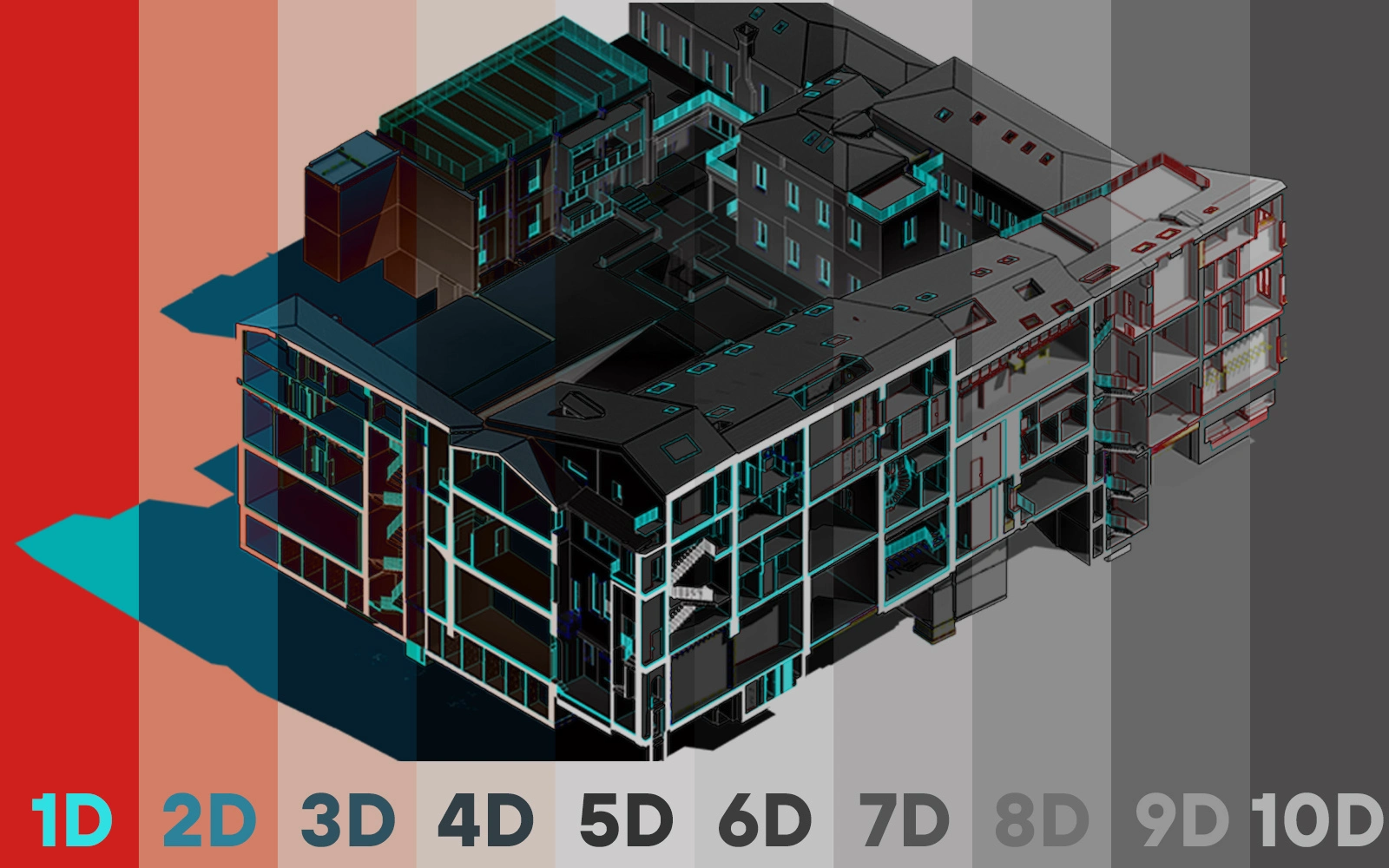

In recent years, the concept of “BIM dimensions” has gradually expanded beyond the now well-established 3D, 4D and 5D, giving rise to a narrative that now refers to 10-dimensional BIM. This evolution reflects the attempt to associate not only time and cost with the digital information model, but also aspects related to sustainability, life cycle management, safety and site construction.

However, the increase in the number of ‘D’s does not correspond to an equally clear evolution in terms of regulations: while international standards favour a structured definition of information requirements rather than the use of dimensional labels, the market and popular literature continue to use these designations as tools for synthesis and communication.

What are the 10 dimensions of BIM?

Before moving on to the practical side hidden behind the needs for synthesis and communication, let’s see what the 10 dimensions are and how they conceptually follow the development flow of a project, starting from the definition of requirements, the production of graphic designs and 3D models, the association of parameters and information useful for project objectives with the models, and finally the use or analysis of this information for a variety of specific purposes in the sector.

1D – Data and information requirements

This is the least mentioned but conceptually fundamental dimension. It concerns data structuring, the client’s information requirements, coding, classification and interoperability criteria. It includes reference standards, required levels of information, data quality and rules for managing the Data Sharing Environment (ACDat).

2D – Two-dimensional representation

It includes traditional graphic designs derived from the model (plans, sections, elevations, diagrams). It does not introduce new information with respect to the model, but represents a technical communication output.

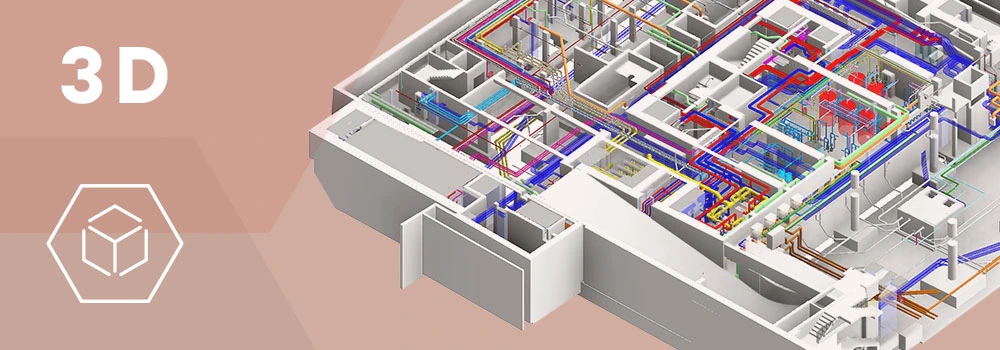

3D – Three-dimensional information model

It is the basis of BIM, the geometric model to which alphanumeric and documentary information is associated. It allows for interdisciplinary coordination, clash detection, visualisation and spatial verification of design solutions, even in systems where mechanical design in a BIM environment is defined by the acronym MEP (Mechanical, Electrical and Plumbing).

The first three dimensions represent the essential basis on which to build the subsequent dimensions. Without them, we cannot talk about a “BIM process” or “digital information management”, as it is called in the latest regulatory updates.

The next two dimensions are now always required and present in a BIM project, albeit with varying degrees of implementation.

4D – Time and scheduling

Link the 3D model to the project and construction time phases (WBS). Support planning, construction sequence simulation, time interference analysis, and work progress monitoring.

5D – Costs and economic control

Integrate the model with economic information such as metric calculations, estimates, cost analyses, and variant control. Enable dynamic links between quantities, times, and costs, supporting cost management throughout the life cycle.

From here on, we enter into areas that are less common and less practised in everyday BIM design.

6D – Sustainability and performance

Associated with environmental, energy and economic sustainability analyses, including LCA, LCC, energy consumption, emissions, comfort and building performance assessments. In some contexts, this dimension also refers to social sustainability.

Sustainability is also a priority for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including Goal 11, which focuses on sustainable cities and communities. The adoption of Green BIM and subsequent advanced dimensions can play a key role in achieving these goals.

7D – Management, maintenance and life cycle

This concerns the use of the model for operation, maintenance and asset management. It includes data on components, manuals, maintenance plans, service life, spare parts and decommissioning. It is central to the operational phase of the project.

8D – Safety and risk management

It links BIM to workplace safety, risk prevention and emergency management issues. It can include scenario simulations, risk analysis during construction and management, and operational safety support.

The latter two dimensions require such a high level of excellence in the application of BIM that few companies can boast of being able to implement them.

9D – Lean Construction and Process Optimisation

It is associated with the integration of BIM and Lean Construction, with the aim of optimising design, construction and management processes, reducing waste, inefficiencies and variability. In this context, the BIM model becomes a tool to support collaborative planning, workflow control and value creation for the client.

10D – Construction industrialisation and DfMA

Commonly linked to the themes of industrialisation in construction, prefabrication, modularity and Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA). In this context, the BIM model becomes the hub of integration between design, production and assembly.

How BIM dimensions are implemented in daily workflows

The construction sector encompasses a wide variety of realities, so it is likely that only some of these dimensions will be relevant. To give a few examples, a design studio will mainly deal with dimensions 1D to 6D, a construction company will add up to 8D, 7D will be decisive for clients and end users, and so on.

Whatever your situation, the effective application of dimensions is based on the same basic principle: having access to the information that a given user needs at a given moment, and this is achieved by having control over the data that generates it.

A project also consists of dozens of models, hundreds of objects, thousands of data points, and chaos is just around the corner: not having all this information clear from the embryonic stage of the project risks compromising its proper development.

The same principle applies to data, and therefore information: the first dimension and analysis of data and requirements is fundamental because it clarifies who needs this data, what its purpose is, how it should be structured, and where to find it. For this reason, it’s the responsibility of every designer to guide them from the starting point (INPUT) to the intended destination (OUTPUT) according to a pre-established path (PROCESS), so that they can become information.

But how is this achieved? There is no single answer to this question, or rather, there are countless answers, as many as there are tools available on the market, from Excel spreadsheets to the latest software, plug-ins or AI applications. The key point, however, is not which tool you use to map and manage data, but to have control over it, organise it and structure it, whatever the scale you want to achieve.